In the previous post https://mathintuitions.com/2024/08/14/orbiting-around-the-truth-approximations-involved-in-newtons-and-einsteins-orbital-equations-part-i/,

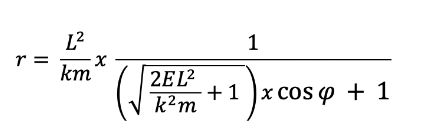

we were able to derive the elliptical orbital path of a planet, where its radial length r is a function of its angle, phi:

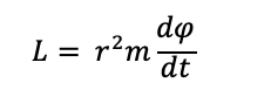

where L, the angular momentum, is equal to

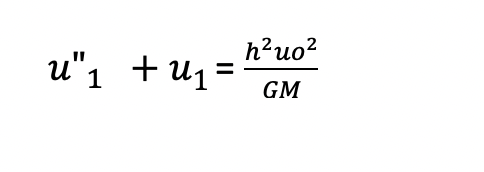

Before arriving at the above expression for r in terms of phi, we arrived at a simpler, more indirect expression for the planetary orbit:

where u=1/r , and k=GMm, with M being the mass of the sun and m being the mass of the planet.

If we take the km/L^2 term and divide numerator and denominator by m^2, we get a modified term in the denominator, h, representing the angular momentum per unit mass (h=r^2x(dphi/dt) as we cancel the m^2 terms present in the numerator and denominator:

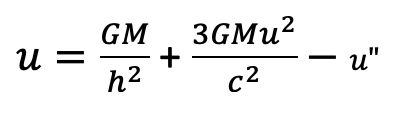

As we will shortly prove, the above expression for the orbital equation in classical physics is modified in General Relativity to include an extra term, 3GMu^2/c^2:

Now we see that both of the above equations have the same form, just with the General Relativity equation containing an extra term. A major goal of the previous post was to derive the orbital equation in a way that has a parallel form to the one derived using General Relativity, and we see that we succeeded

In order to arrive at the expression

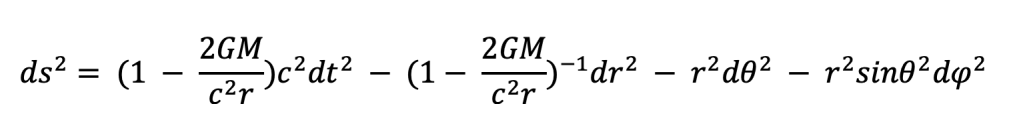

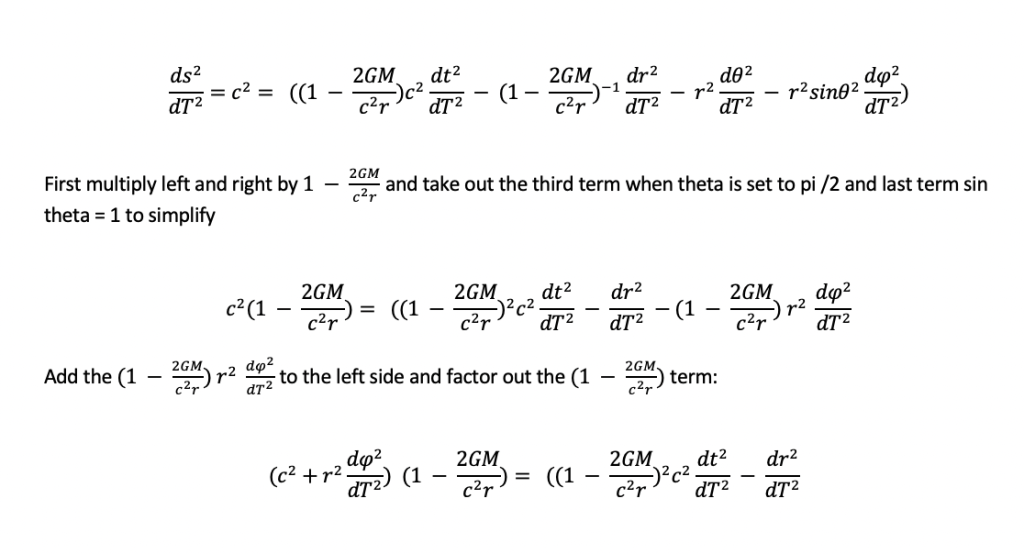

we must start with the Schwarzschild metric:

This metric equation above is the conversion factor between someone very far from the gravitational mass and someone very close to it. No matter the coordinates used for the person far from the mass, we will always get the same invariant space-time length, ds, due to this metric equation being a tensor. This metric already encodes the Lorentz transformations for movement that are present in special relativity’s flat Minkowski space, which has the metric

The term dr in both metrics is defined to be a unit of radial lengthening in flat spacetime. However, dr is not the same as the actual physical distance when we are in a gravitational field in curved spacetime; when in a gravitational field centered around mass M in the Schwartzschild metric, we see that the dr term is multiplied by a factor, and it is this factor that helps us convert what 1 dr of flat space distance is worth in the curved, gravitational space distance. As r, or the distance from the gravitational mass, gets closer and closer to the gravitational source and approaches 2GM/rc^2, we get a higher and higher value for ds, the “physical distance” measured, meaning that 1 unit of dr for someone close to a gravitational mass has a very big physical distance (as shown by Flamm’s Paraboloid in a previous post https://mathintuitions.com/2023/08/09/its-all-relative-a-different-visualization-for-the-warping-of-space-time-in-general-relativity/).

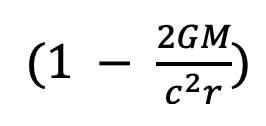

In summary, if we want to consider proper space, whereby dt=0 and we are measuring solely across space without any time passing, we find that when we are very close to the gravitational mass we get a very, very big number for proper distance when dr is 1 because of the factor

getting smaller and smaller in the denominator as r approaches 2GM/c^2 from positive infinity (where spacetime is flat).

Likewise, someone who measures 1 dt very far from the mass in flat spacetime would have to convert by this factor

to find the experience of time for someone close to the mass (located at a distance r from the mass), and as r approaches 2GM/rc^2 from positive infinity. We do see that 1 dt experienced by someone very far from the gravitational mass results in an extremely small passage of time for someone close to the mass.

Now we can apply the Lagrangian, built from the Euler-Lagrange equations (to see a derivation of the Euler-Lagrange equation, visit https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sFqp2lCEvwM&t=44s and for the Lagrangian visit https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4uJaKJASKnY&list=PLX2gX-ftPVXWK0GOFDi7FcmIMMhY_7fU9 . These equations will help us solve for the orbital path by first getting some constants of motion in the Schwartzschild metric of:

Now, the Lagrangian to be minimized is T- V, where T is the kinetic energy and V is the potential energy, but there is no longer the V term because the Schwartzschild metric already encodes the gravitational potential energy as curvatures of spacetime. Thus we only need to minimize T, the kinetic energy.

By minimizing the kinetic energy between any two points, we will get the maximal proper time for the object’s motion and hence the geodesic, or shortest path in spacetime, that an object will take in the absence of external forces. We get maximum proper time by minimizing the kinetic energy because the path with the lowest kinetic energy corresponds to the lowest average velocity (and thus the absence of accelerations) out of all the paths possible that record the same beginning and ending time, which thereby would correspond to the path of the maximal proper time since the lower your velocity, the more proper time you record.

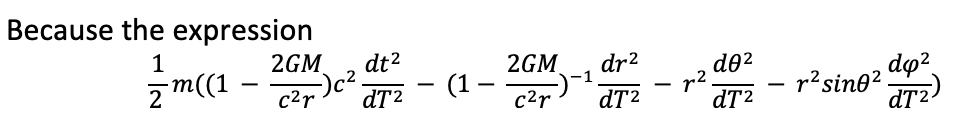

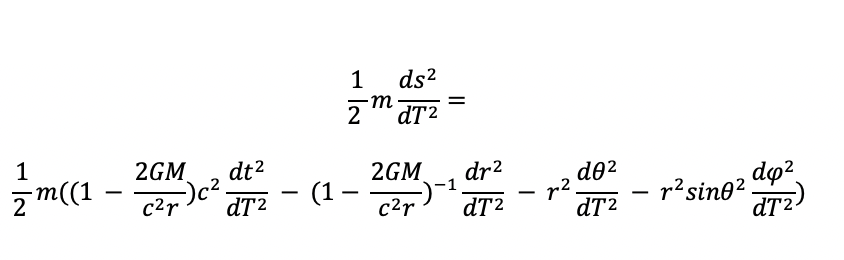

So we want to minimize the kinetic energy of term 1/2mv^2, so we must divide ds^2 by the proper time DT^2, and and multiply each side by 1/2 m. In fact, we don’t really need to keep the mass in since the mass is a constant and, if we minimize the 1/2 v^2, we would minimize the kinetic energy anyway, but we will fully express the kinetic energy term anyway.

So:

The Lagrangian above only contains the first derivatives of the various coordinates so that simplifies things a lot:

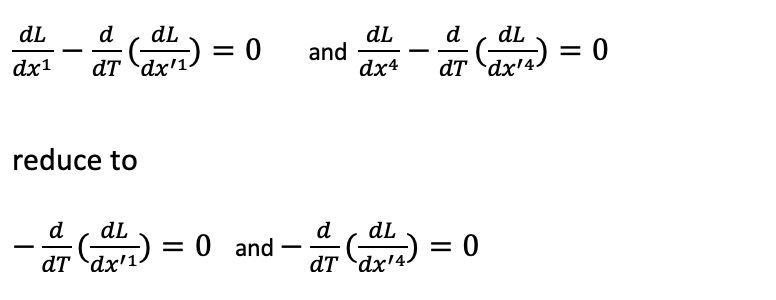

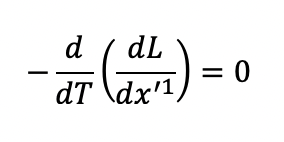

Using the Euler LaGrange equation to extremize the function, we apply:

where “a” is the specific coordinate we are focused on and the primed notation signifies the derivative of that coordinate with respect to proper time.

This will result in applying the above equation 4 times, one for each coordinate. Luckily, as we will see, we actually only need to perform the above equation for the first and fourth coordinates listed below:

deals only with the derivatives of the first and fourth coordinates, which are

, our Euler LaGrange equations for these coordinates:

What about the second and third coordinates,

For the r variable (the second coordinate), we will see that we don’t need to apply the Euler La Grange equation to it, luckily, in order to get the orbital equation of motion that we are looking for (it would be extra messy to do this since not only do we have a dr/dT term, we also have the r variable to deal with too). For the theta variable, we are going to set theta equal to pi/2, which we can do because of rotational symmetry (we can always tilt our axes such that we are at pi/2). Thus our dtheta/dt term is 0 and we don’t have to consider applying the Euler La Grange equation to the theta coordinate. By setting theta equal to pi/2, we also get the sintheta term in the metric to be 1, thereby simplifying the term multiplying the 4th coordinate.

So ultimately we only have to apply the Lagrangian to our first and fourth coordinates, time and phi.

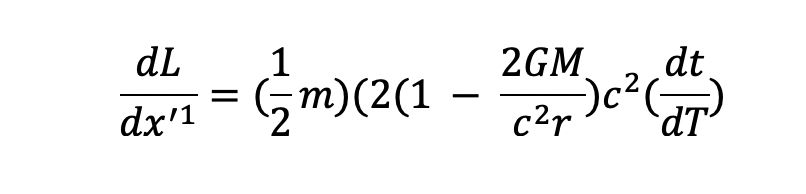

If we take the first coordinate’s (time’s) kinetic energy,

and take the derivative of it with respect to the dt/dT, we get:

And simplifying and rearranging we get:

Plugging the above term into the Lagrangian equation below

yields the following for our first coordinate, t:

Of course derivatives of constants like mc^2 are 0. But because the above derivative is 0, it also must mean that the derivatives of those parts that are not constants (those parts that include the time derivative and radius terms which are dependent on changes in T, the proper time) are also 0.

So, therefore, the stuff after the constants mc^2 must be 0 too :

Now let’s integrate the above with respect to dT, the change in proper time.

We then get:

where k is a constant., since whenever you integrate something that equals 0, you get a constant k, since the derivative of a constant is 0.

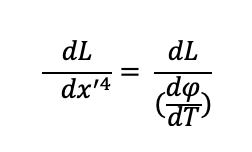

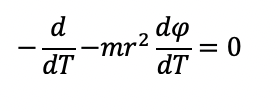

Now we will apply the Euler La Grange equation to our fourth coordinate, phi:

which, as previously stated, reduces to the following since the expression has no functions of phi itself but only its derivatives with respect to proper time:

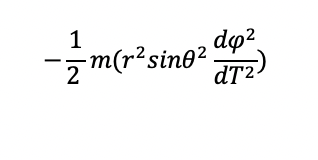

This fourth coordinate is the final term present in our kinetic energy expression in the Schwartzschild metric:

And thus we are looking to minimize:

We have simplified things immensely by setting theta at pi/2 so our sin(theta) term becomes one, and we only have to minimize:

First we must solve for

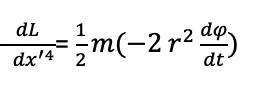

This equals

which simplifies to

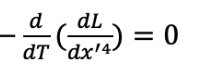

Plugging this into our Euler La Grange equation,

, yields:

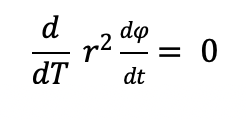

Because the above derivative is 0, it also must mean that the derivatives of those parts that are not constants (those parts that include radius and phi derivative which are dependent on changes in T, the proper time) are also 0.

So we have:

After we integrate both sides with respect to proper time T , we find that

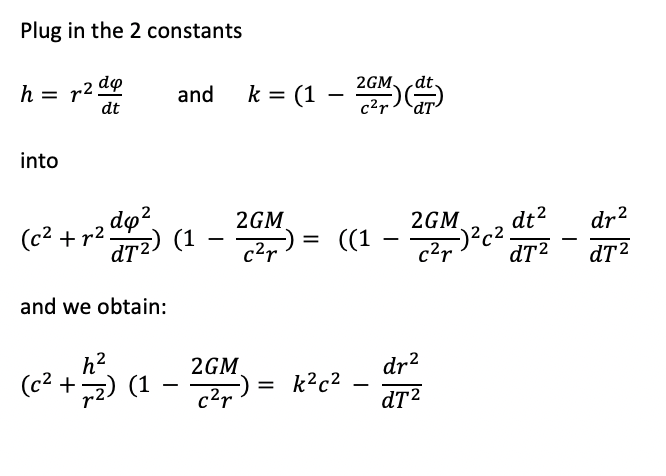

We can utilize these constants in the velocity formula. Knowing that the 4 velocity must equal c, we plug in our constants k and h below:

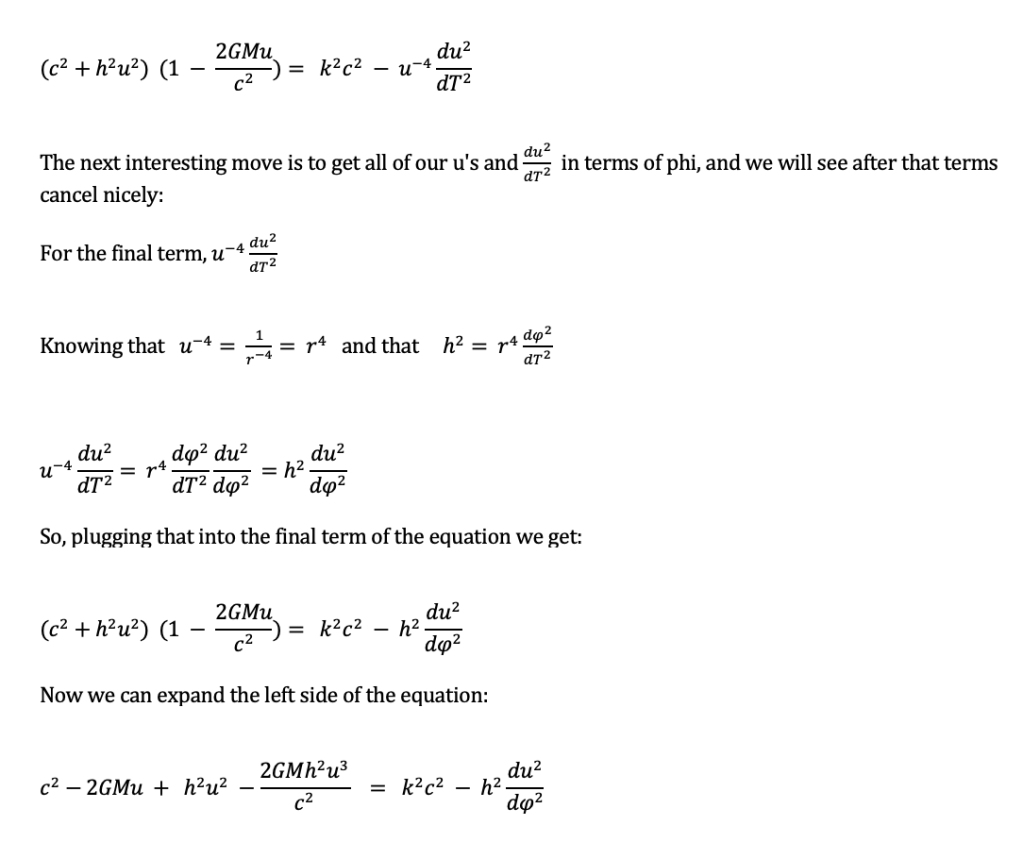

to get the following:

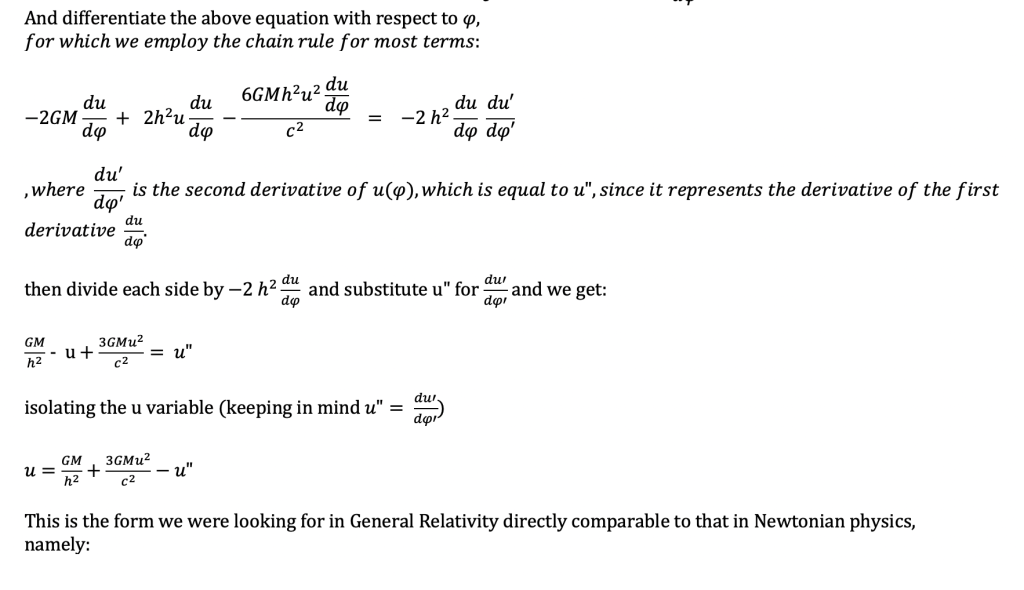

Now, how can we solve for u= 1/ r ?

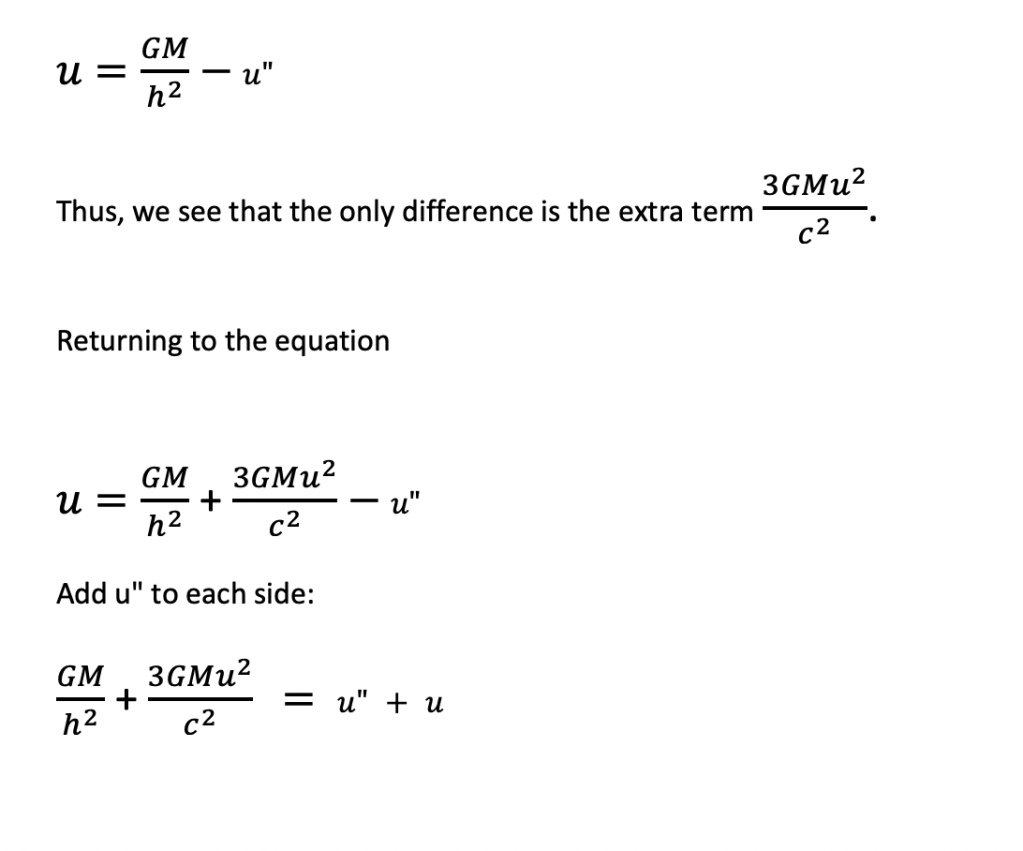

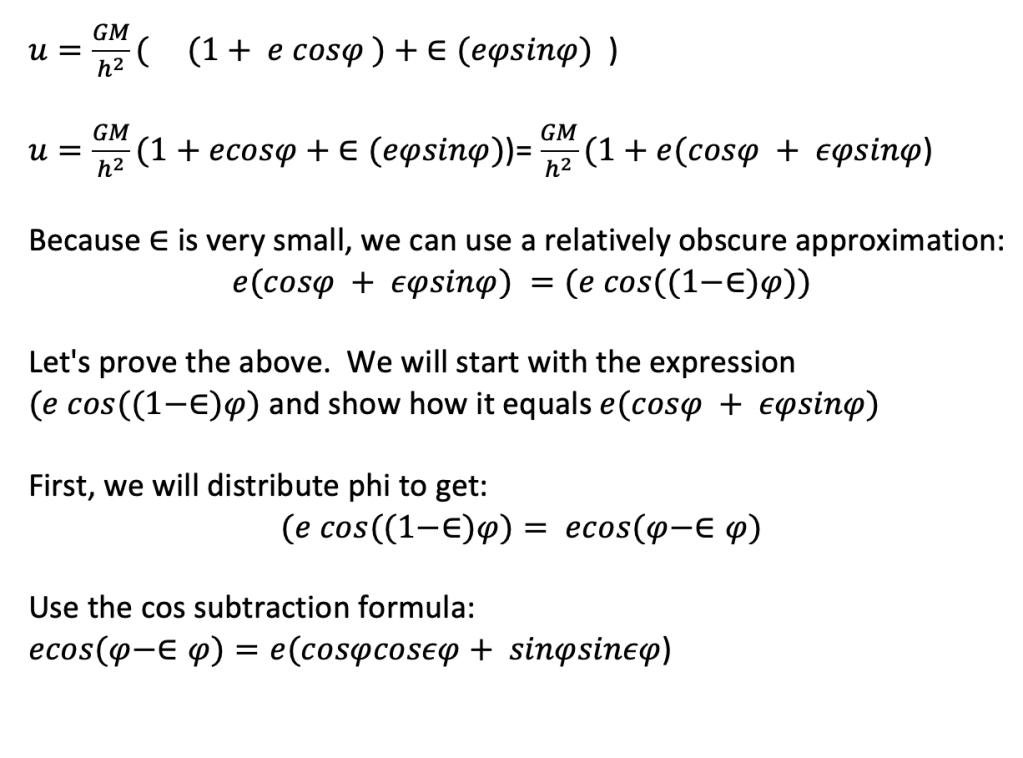

We introduce a “perturbation term,” a term that must be very small (for more on how to use perturbation theory in solving differential equations, visit https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1y_oC-8to0U). Already, the extra term 3GMu^2/c^2 is super small.

Let the perturbed term be equal to

The reason for letting the perturbed term equal this is that it makes it much easier to solve then if we just had the perturbed term equal to 3GM/C^2. Now you don’t get cross terms u0u1 to first order in E. Moreover, as required, this perturbation term is dimensionless as the units cancel. Substituting our perturbation term into the equation, we get:

We know the solution to the above when E is 0: it just reduces to the Newtonian equation!

Now we want to see how the solution deviates from the Newtonian equation with our perturbation term being a very small, but non-zero.

We already know what the solution is when E is 0, which is the Newtonian case.

Now we can figure it out when E is slightly more than 0 and we solve for du/de, or u1.

So how do we find u1? We plug the following 2 equations (1 and 2) into our original equation (3) for any terms that contain u or u”

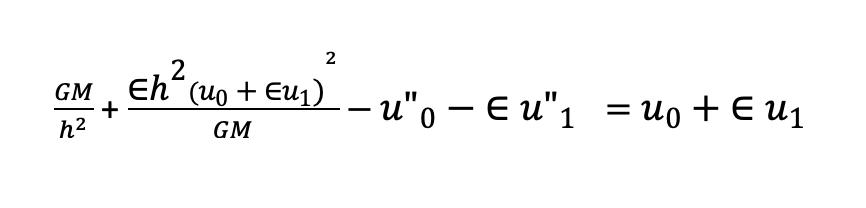

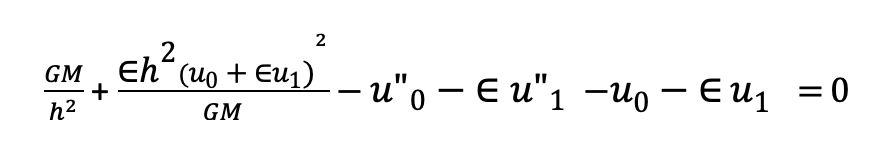

So after we move u” to the left hand side and plug 1. and 2. into 3, we get:

Let’s move everything on the right to the left side of the equation:

When centered around E=0 it reduces to the Newtonian equation as expected:

Now, returning to

Gather all terms that are first order in E ( which means E^1) and take the derivative with respect to E, and set equal to 0 since everything equals 0 already. Any terms without E will equal 0 since they are constants when we take the derivative with respect to E and any terms with E^2 will equal 0 too, because E is already so small such that E^2 would be infinitesimally smaller than the already infinitesimal E. After we take the derivative with respect to E and cancelling E^2 terms and constants, we get:

Now, rearranging:

We will return to the above equation shortly, but first we must substitute for the term Uo by using the following facts:

Remembering that when E=0 in:

we end up getting the Newtonian orbit approximation for Uo:

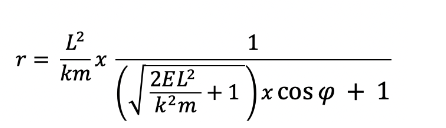

and by knowing r is equal to:

we then know that Uo=1/r is equal to

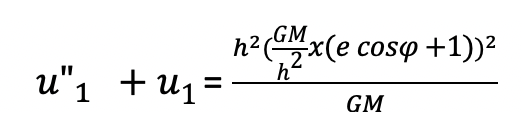

Finally, plugging the above expression for Uo back into our equation for the terms that are first order in E,

we get

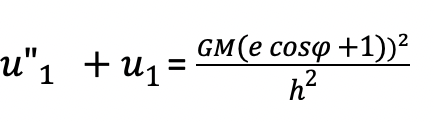

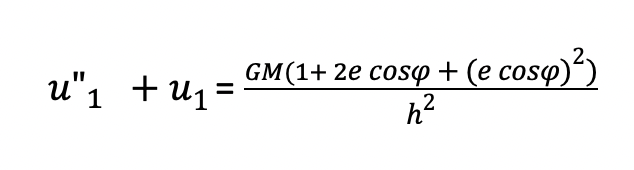

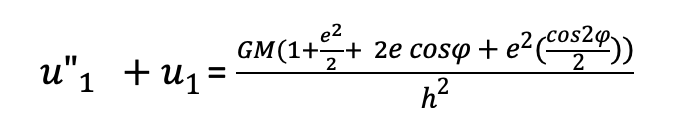

which simplifies to

We can express the right-hand side of the equation as three separate terms:

Our whole goal is to find what u1 equals to get a better approximation for what the orbits actually equal in General Relativity perturbation equation: U= Uo +EU1

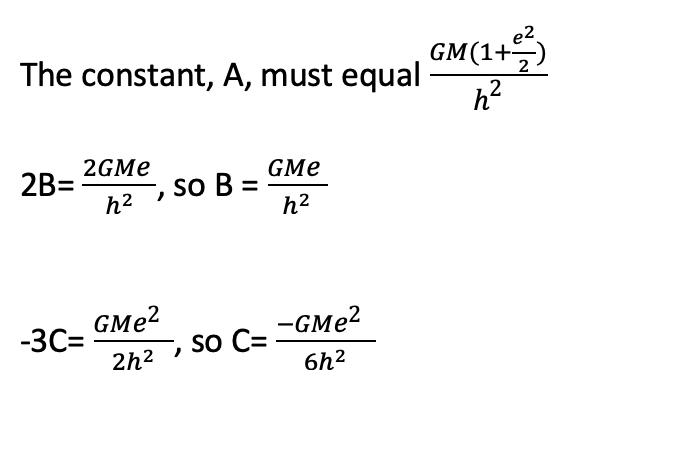

We know that the above equation in bold says that u”1 + u1 equals 3 separate terms, but let’s be more general and say that out of the three terms, the first term is a constant term A, the second term is Bcosphi and the third term is Ccos2phi.

We must choose a suitable u1 so that u1 + u1″ will equal the general form of A +Bcosphi + Ccos2phi. Once we choose the right way for u1, then we can solve for A, B and C by comparing them with the factors in the above bold equation.

Finally, we can solve for u= uo + Eu1 by plugging in our known values.

Returning to our general equation we chose for U1 that worked:

Now the only term that really matters in the new factor multiplying E is the (GMe/h^2)(phi)(sinphi), which is not periodic. As phi grows, this term continues to grow and grow due to phi increasing; the other terms do not grow and are thus very, very tiny since they are all multiplying E, which is so infinitesimal.

So, factoring out the GM/h^2 term and ignoring the other terms which are so exceedingly small , we can get. a simplified equation:

We want to know what 2piE is equal to, since that is the additional amount to the normal period of 2pi. This means that the ellipse is rotating and it is taking longer for the radius to get back to the original point due to the rotation.

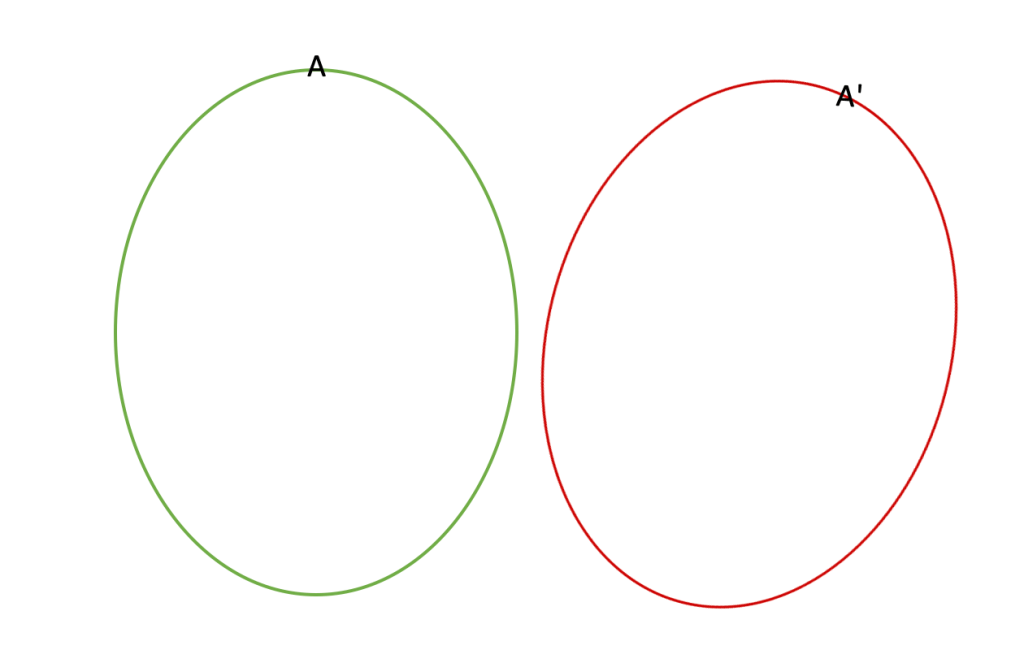

In the figure below, we see that if in the green orbit, the planet would start at A= 0 degrees and end at A=2pi (one full revolution around the ellipse) as the planet revolves around its elliptical orbit. However, because General Relativity shows us that the planetary orbital period due to the Schwartzschild metric is actually elongated by an extra +2piE, this means that it starts at point A but must travel 2pi + 2piE to reach point A again (now point A is shown as A’ after the rotation by a distance of 2piE in the rotated red ellipse). So, the orbit must go an additional distance beyond the normal 2pi to reach its starting point again:

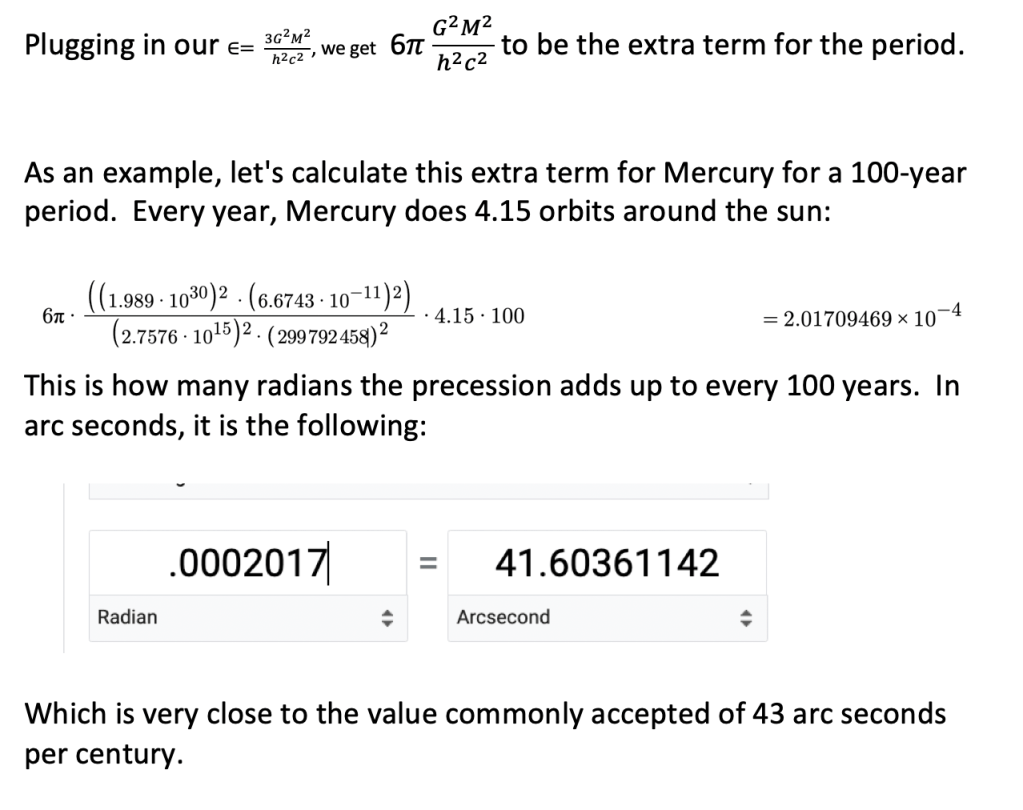

So let’s figure out what 2piE is equal to by plugging our preset value of E into 2piE:

Thus we have shown how much of Mercury’s precession is from the General Relativity equations that account for the curvature of space-time due to the large gravitational mass of the sun. The extra 43 arc seconds couldn’t be explained until the Schwartzschild metric was used.