A few weeks back I came upon the claim that a parabola is just an infinite ellipse, with one focus of the ellipse at infinity.

I wasn’t entirely convinced until I started to look deeper into the properties of ellipses with the help of Desmos.

Here is a picture of an ellipse from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ellipse-param.svg#/media/File:Ellipse-param.svg

The ellipse is defined as the locus of points whose sum of their 2 distances to the two focal points F2 and F1 is constant at “2a.”

“a” is first defined as the distance from the center of the ellipse to the point (either left-most or right-most, in the picture above) along its major axis (the axis most stretched out- in this case along the x-axis). “b” is the distance from the center of the ellipse to the point (either highest or lowest in the picture above) along its minor axis (the axis not quite as stretched- in this case along the y axis). The ellipse may also have its major axis in the vertical direction and its minor axis in the horizontal direction.

The two foci F2 and F1 must be the same distance from the center of the ellipse. The reason why the foci must be the same distance from the center is to preserve the idea that all points are a sum of 2a distance from the foci. To prove the fact that the foci must be the same distance from the center (let’s call that distance “c”), let’s start with the left most point of the ellipse along the major axis. Clearly, the distance of that point to F2 is (a-c). The only possible place F1 can therefore be located in order to preserve the fact that the sum of the 2 distances from that point to the two focal points is 2a is at the point (a +c), since (a-c) + (a+c)= 2a.

Now, because the foci are symmetric at +/- c from the vertex, they each must be the same distance from the uppermost point on the minor axis. If they must be the same distance from the uppermost point on the minor axis (and bottom point on the minor axis as well), then they each must be “a” units from that point in order to get the sum from that point to be 2a. In the picture, this “a” is shown as the hypotenuse of the triangle that links F1 and F2 to the uppermost point on the minor axis.

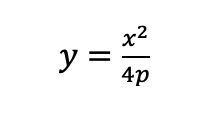

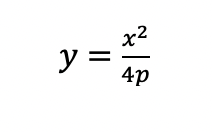

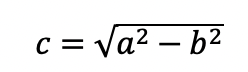

An important idea is that the ellipse has an eccentricity of c/a, where ”a” is the hypotenuse from the focus to the upper or lowermost point on the minor axis, and b and c are the sides of a right triangle, as shown in the image. Thus we can use the Pythagorean Theorem to solve for c, the distance of the center to the focus:

As the foci move towards the center, the distance “c” approaches 0 and a circle is formed (with one focus at the center). As the foci move further and further from the center, c approaches “a” and you get a very eccentric ellipse, or one that is very stretched out.

The ellipse equation is:

A good derivation of this equation is available at:https://openstax.org/books/college-algebra-2e/pages/8-1-the-ellipse.

The eccentricity of c/a that we defined above is actually a fundamental property of all conic sections. Remarkably, eccentricity can be defined in two seemingly disparate ways. The first way to define eccentricity is to perform the aforementioned process: take the value of c, which represents the distance from the center to the focus, and divide it by a, which represents the distance from the center to the vertex (for an ellipse, there are two vertices, each being endpoints on the major axis; for a parabola, there is only one vertex). For any given ellipse, the eccentricity, or value of c/a, is a constant value between 0 and 1; for any given parabola, the eccentricity is a constant value of exactly 1; for any given hyperbola, the eccentricity is greater than 1; for any given circle , as we already saw, the eccentricity is 0. There is a great visualization of how eccentricities relate to various conic sections here: https://www.geogebra.org/m/psCVp4RR

The second and equivalent way to define eccentricity of any conic section is to take any point’s distance to the focus and then divide that by the point’s distance to a given line known as the directrix. For the ellipse, there are 2 directrices- left and right (or, up and down, depending on the ellipse’s orientation)- for each left and right focus.

We can prove that the 2 directrices lie at -a/e and +a/e for an ellipse centered at the origin, where e=c/a. The assumption is that you can find the directrix by placing it a certain distance from the focus in order to maintain a constant ratio between a point’s distance to the focus and that point’s distance to the directrix.

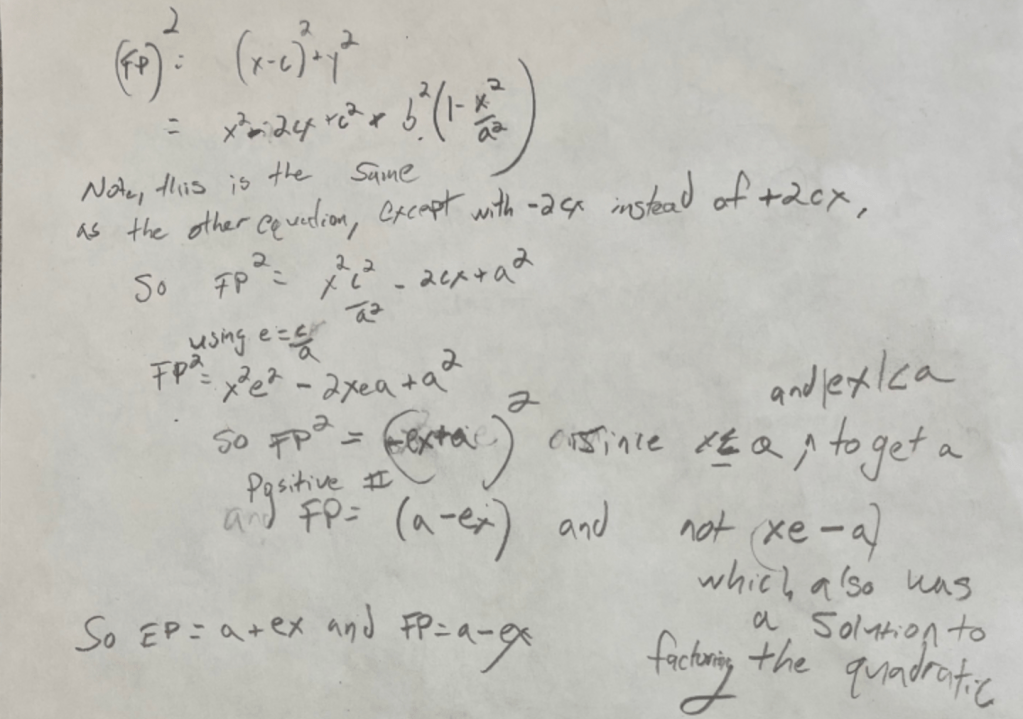

The following proof is to first show how the directrices of the ellipse can be proven to be located at +/- a/e. It is based on an excellent one that I found online that I can no longer locate, but which I also modified and added to extensively. Below, I wrote the letter e for eccentricity, which is initially defined as c/a, or the distance from the center to the focus divided by the distance of the center to the vertex. Let’s find out why the directrices of the ellipse lie at +/-a/e:

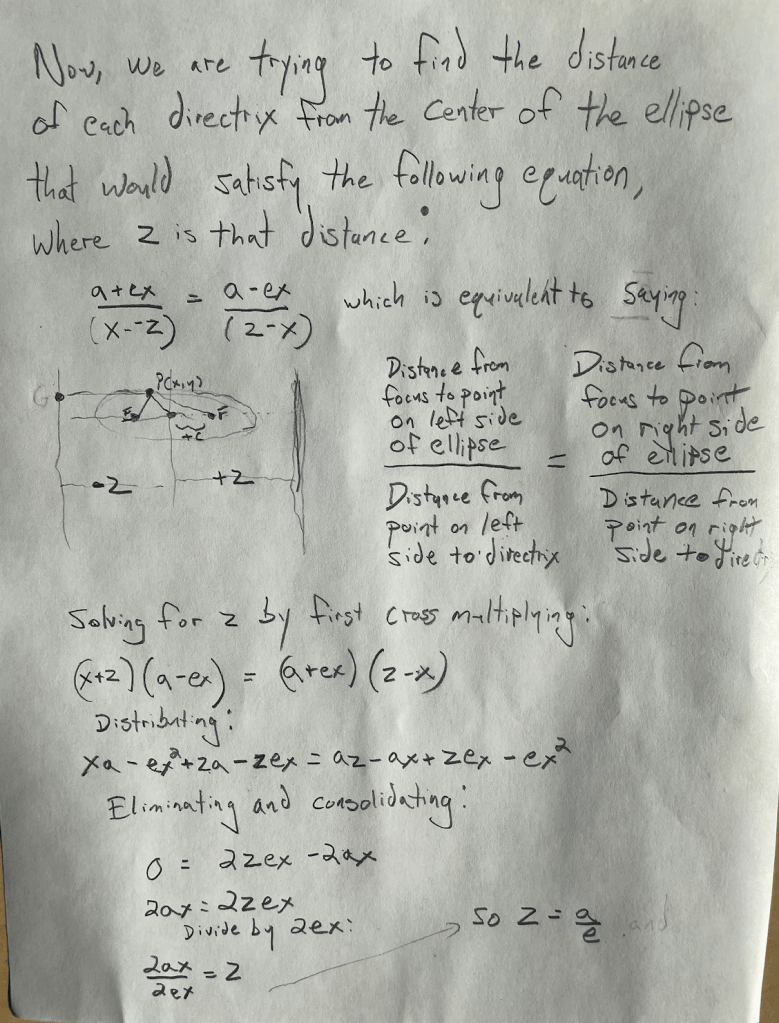

So far we have shown that the distance from the left focus to any point on the left side of the ellipse is equivalent to (a + ex), and the distance from the right focus to any point on the right side of the ellipse is (a-ex). Now we want to figure out where to put the two directrices, left and right, such that the distance between the focus to a point on the left side of the ellipse divided by the distance from that point to the left directrix equals the distance between the focus to a point on the right side of the ellipse divided by the distance from that point to the right directrix. We will label +/- z the distance from the center of the ellipse to the position of the right and left directrix, respectively, and solve for what z is as shown below:

We have just shown that the right directrix must be a distance of a/e from the center of the ellipse, and that the left directrix must be a distance of -a/e from the center of the ellipse.

Now that we have found the distances of the two directrices from the center of the ellipse, we can see if the second method of calculating the ellipse’s eccentricity (defined as the ratio of the distance from the focus to a point divided by the distance of that point to the directrix) yields the same result as the first method of calculating eccentricity (which is just taking c/a=e ). So, let’s divide the generalized distance of a point to its focus by the distance of that point to its relevant directrix: We can do so by doing the following:

We have just proven that, not only do the directrices of the ellipse lie at +a/e and -a/e, but also that that the distance of any point to the focus divided by the distance of that point to the closest directrix is equal to e, the eccentricity. Thus, the second method of calculating eccentricity (the distance of the focus to a point divided by the distance of the point to the directrix) gives us the same value as the first (which uses 2 simple parameters: c/a=e)

To summarize so far, the eccentricity of the ellipse can be defined either as the distance of e=c/a, which equals the distance of the focus to the center divided by the distance of the vertex to the center; or, it can equivalently be defined as the distance of any point to the focus divided by the distance of that point to the closest directrix, which also remarkably equals e=c/a.

This seems almost like a miracle to me: there is nothing obvious that makes it necessary for both of these methods to calculate the same exact number, though there is probably some hidden logic I’m not completely seeing.

We can finally begin to address the main claim of this post: that a parabola is actually an infinite ellipse. To do so, we must utilize both of the different yet equivalent definitions of eccentricity. Most commonly, the first method of calculating eccentricity is used to show the eccentricity of the ellipse, since the parameters “a” and “c” uniquely belong to ellipses and hyperbolas, but not parabolas. So it is easy to just take c/a=e to find the ellipse’s eccentricity. On the other hand, a parabola’s eccentricity of 1 is more often depicted through the second method of calculating eccentricity that takes the ratio of the distance of the focus to a point and then divides that by the distance of the point to the directrix (and to obtain the eccentricity of 1, both these distances must be equal for all the parabola’s points). This second method of calculating eccentricity is done for parabolas since parabolas don’t seem to have the same parameters “a” or “c” that characterize the ellipse and which are used in the first method to calculate eccentricity.

However, once we employ numbers that approach infinity for the distance of the focus and major axis of the ellipse from the center of the ellipse, we can also obtain the parabola’s eccentricity of 1 using he first method of calculating eccentricity that uses the two parameters, “c” and “a” that supposedly belong uniquely to ellipses.

In order to show that the parabola is an infinite ellipse, we start by redefining the ellipse’s eccentricity c/a, as the handwritten proof below does. This time, we construct the major axis along the y axis and the minor axis along the x axis, and then ensure that the focus is placed at the origin. We then will then let “a”, the distance from the center to the vertex along a major axis, approach infinity and see what we get:

We have just proven two important facts: firstly, that, when “a,” or the distance from the center of the ellipse to the end point of its major axis, approaches infinity, the eccentricity of the ellipse approaches 1 (which is the same eccentricity of a parabola). Secondly, we have proven that the final equation shown above that describes an ellipse with an infinite major axis looks suspiciously similar to the equation of a parabola, which is:

where “p” is the distance of the parabola’s directrix from the vertex and equivalently represents the distance of the vertex to the focus.

To summarize, for the ellipse with “a” pushed to infinity, we have:

Remember that the equation above represents an ellipse with one focus pinned down at the origin and another focus pushed out to infinity. Though we only pushed the variable “a” out towards infinity, by doing so it also pushes c, or the distance from the focus to the center, towards infinity as well, since

and as “a” goes to infinity, so would “c.” So one focus is pinned at the origin and the other focus is pushed out to infinity.

The term a(1-e) is indeterminate, since as “a” is pushed to infinity, e approaches 1 and thus the term a(1-e) represents a number approaching infinity times a number approaching 0. There’s no great solution to this until, instead of approaching infinity, we decide to have “a” represent a very, very large number (in fact as large as we want) and to have “c” represent a very very large number, that is always a fixed distance away from “a”, thereby keeping the term (a-c) constant.

Using the equation for the ellipse with “a,” pushed to infinity:

we can plug in c/a for e:

then distribute:

Now, even though both “a” and “c” are headed towards infinity, if we keep a-c as a fixed number, we can get a much better picture of the relationship between infinite ellipses and parabolas.

The equation above is indeed a parabola of the form

with p=(a-c) and the graph shifted down by (a-c).

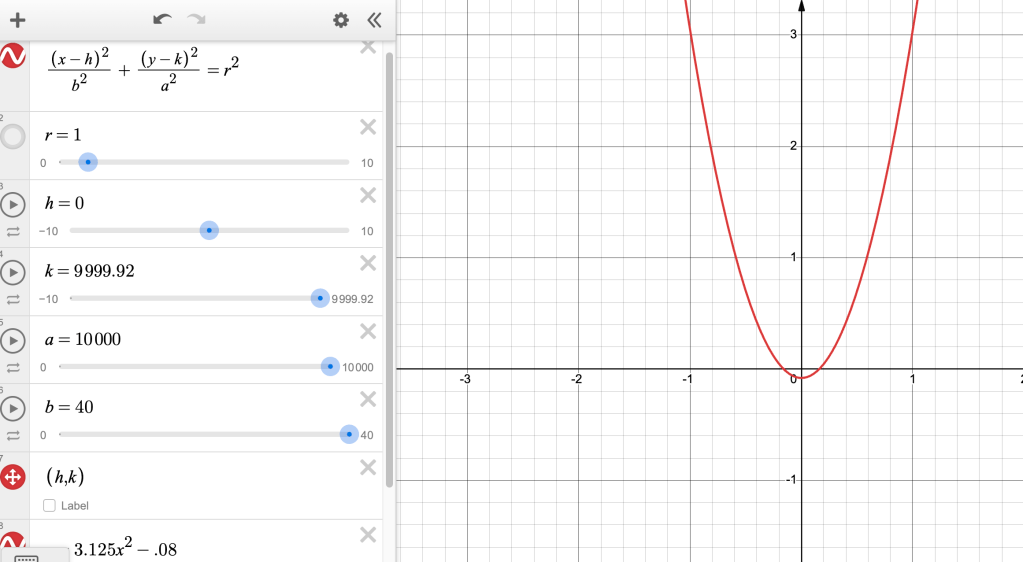

Now we will attempt to relate ellipses whose “a” values get very large and whose (a-c) values are fixed (in this case I randomly chose (a-c) to be fixed at .08:

Using Desmos, I experimented with some values of the ellipse “a” = 10,000, b= 40, and c therefore equal to

=

Here is what I got, and I will now explain each parameter more fully:

As in the proof, we first have to center the ellipse at +c, so we let the parameter k=c=9999.92 as shown below.

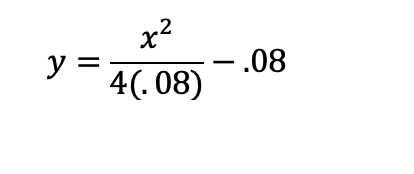

Additionally, you can see at the bottom left of the image I plugged in the equation of a parabola

with the same parameters of the ellipse a=10,000 and c=40:

This implies that the directrix of the parabola, p, = .08 units from the vertex, and that the vertex is .08 units from the focus since all points on the parabola are equidistant from both the directrix and focus. Additionally, the shift down of the graph -.08 implies that the focus of the parabola is at the origin (just like the bottom focus of the ellipse is pinned to the origin), the vertex is located at -.08, and the directrix is located at 2(-08) where it intersects the y-axis at that point.

Now 1/4(.08)= 3.125, so we will substitute that into our parabola equation above to obtain the equation I plugged into Desmos for the parabola at the bottom of the above image:

.

In summary, the ellipse that is described as

and the parabola described by

are indistinguishable in the image below:

In fact, even if you continuously zoom in, it is hard to find any difference. Take for example at the 1/10th level, there is still 0 difference between the curves.

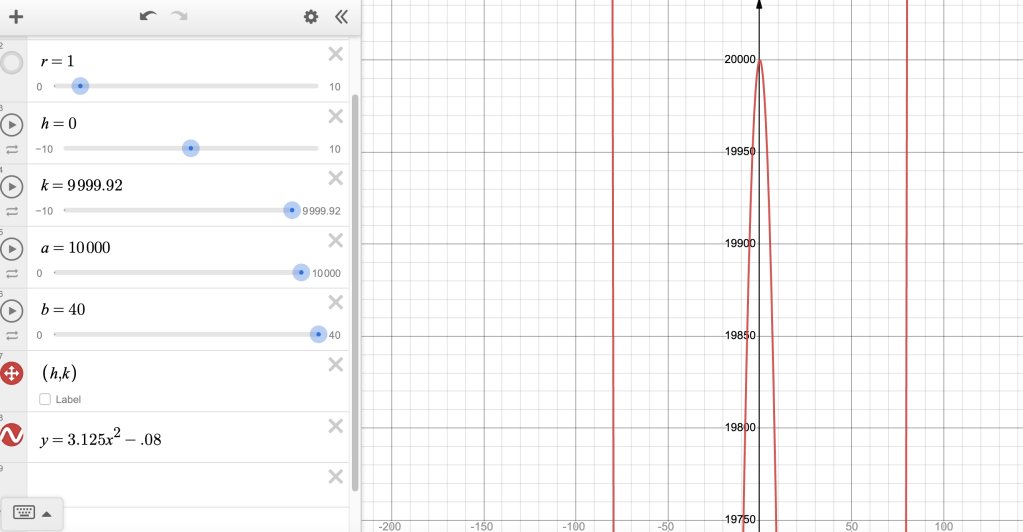

However, as you move way up the y-axis, you find that there are indeed two shapes that diverge. By the time you are at the center of the ellipse at around 10,000, there is clearly one ellipse (the inner two curves) and one parabola (the outer two curves).

And by the time you have traveled across the major axis of the ellipse whose distance is 2a or 2(10,000), the ellipse closes while the parabola continues.

As you might imagine, when we make the ellipse parameters “a” and “c” larger and larger while still maintaining a fixed distance between them, the closer and closer we get to a parabola throughout the entire range. As “a” and “c” get infinitely large, the ellipse never closes at all; and if we can assume that we can arbitrarily set some fixed distance between these two parameters as they race off to infinity, then (a-c) is a fixed number that represents “p” in the parabola equation, as well as a downward shift by that fixed amount (confession: I’m not sure if you are allowed to keep (a-c) constant as both race off to infinity, but it seems to work well for this very informal proof!)

Now we can return to the parabola’s eccentricity. We previously discussed that there are 2 equivalent ways to define eccentricity for the ellipse, but for the parabola , eccentricity is only typically defined via the second method: that is, when you take the ratio of the distance from the focus to a point on the parabola and divide that by the distance from the point to the directrix, you get 1. We see this in our example above, with the focus being .08 away from the vertex and the vertex also being .08 from the directrix, to obtain .08/.08=1. We can do the same for any other point on the parabola and it would always equal one.

We now can also define the parabola’s eccentricity via the first method of calculating an ellipse’s eccentricity, which simply takes the ratio of 2 parameters of the infinite ellipse: c/a. Assuming a-c is a fixed value, as “a” and “c” both get arbitrarily large towards infinity, c/a=1. To show c/a=1 as “a” and “c” get arbitrarily large, I will use some real numbers and assume that we want a-c to be the constant value of 20. If we first choose c=10 and a=30, then c/a is only 1/3. But if we instead make both “c” and “a” much larger at c=10,000 and a=10,020, then c/a =.998, which is very close to one. If we continue to enlarge both c and a with a fixed distance between them, c/a becomes 1, and thus the parabola’s (or ellipse’s?) eccentricity is 1.

To summarize, we have shown that as we push the ellipse’s parameter “a” to infinity, the ellipse’s eccentricity approaches 1 (in other words it becomes a parabola, whose unique eccentricity equals 1). A key assumption is that the ellipse’s parameter “c” also races off to infinity, but always at a fixed distance from “a.” This fixed distance of (a-c) becomes the parameter “p” in the parabola equation, telling us the distance of the directrix from the vertex and also the distance from the vertex to the focus (since both distances must be equal to have e=1, using the second method of calculating eccentricity).

Can we get the distance of the directrix from the vertex of the parabola by just using information contained within the infinite ellipse, without any foreknowledge of the actual equation of the parabola? We actually can! We have already shown that the infinite ellipse has an eccentricity that approaches 1; that is, e=c/a=1. We also assumed that (a-c) is a fixed distance, and showed how this can still be true even as c/a approaches 1 when both c and a race off to infinity. Finally, we know that the position of the directrices of the generalized ellipse is at +/- a/e= +/- a/(c/a). Now, as “a” and “c” race off to infinity, a/(c/a) seems to be equal to infinity/1, since c/a approaches 1. However, something else is seen to happen. Given that we set (a-c) a fixed distance apart as both race off to infinity, a/(c/a) approaches a + (a -c) ! So, the directrix of the infinite ellipse is located (a-c) units past its vertex at “a.” This means that if we are at the vertex of the infinite ellipse, we can move a distance of either (a-c) inwards to arrive at the focus since that is what (a-c) is defined as, or we can move a distance (a-c) outwards past the vertex to arrive at the directrix. This is the definition of a parabola: when we are at the vertex of the parabola, the directrix and the focus must be equal but opposite lengths away (this length is “p” in the parabola equation).

Below, we find that a/(c/a) gets closer and closer to a +(a-c) as we make “a” and “c” larger and larger while still assuming (a-c)=20. This means that the directrix location approaches the directrix location of a parabola, which is exactly (a-c) (or +p, in parabola terms) units past the vertex (which is “a” units from the center of the ellipse).

So this gets closer and closer to 10,000 +20, or (a + (a-c), as “a” and “c” get arbitrarily large with the fixed distance of 20 between them.

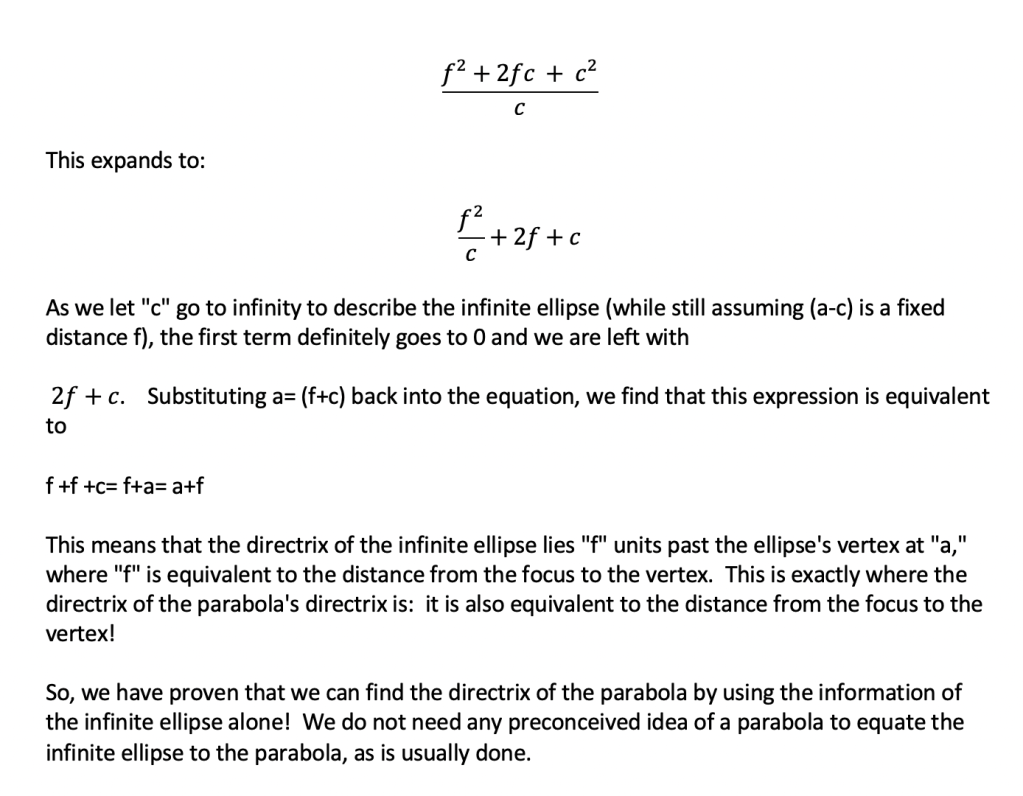

A way to prove that a/(c/a) equals a + (a-c) as “a” and “c” are pushed to infinity is to first use the knowledge that the generalized ellipse directrix’s is located at a/e=a/(c/a) units from the center of the ellipse. Then, as mentioned, we keep (a-c) a fixed distance- let’s relabel this distance of (a-c) as “f.” So if (a-c)=f, then a=f+c. We can now plug in (f+c) for a in the equation with the directrix: a/e= a/(c/a)= (f+c)(f+c)/c. If we expand, then we get the following expression:

But in order for the ellipse to truly never close, we must imagine that “a” and “c” are racing forever to infinity, and that we are continually shifting up the ellipse’s bottom vertex (which is racing towards negative infinity) in order to place the focus of the ellipse at some predetermined point (we chose to shift up by +c and place the focus at the origin). Additionally, the vertex is the fixed (a-c) units away from the focus, whatever we choose (a-c) to be. (a-c) is equivalent to the parameter “p” in the parabola equation, which represents the distance of the vertex to the directrix and the distance of the vertex to the focus.

So, in the example we used, the parabola can be seen as an ellipse that is infinitely expanding, where one focus is forever being shifted up to be pinned at the origin, while its topmost focus is forever racing off towards infinity at some fixed distance from the topmost vertex. This is more poetry than math in the end: a static parabola can be seen as an infinite ellipse that is also being infinitely stretched and infinitely shifted. This allows us, if you will, to see one end of infinity!