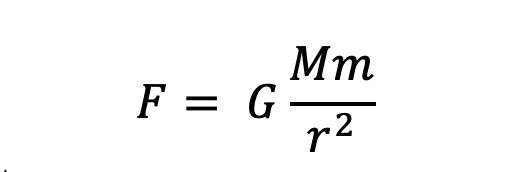

It is a well-known truth that the gravitational force, F, is equal to:

where G is the gravitational constant.

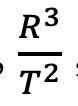

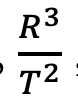

The three laws of the German mathematician and physicist Johannes Kepler paved the way for the Law of Gravitation; The first Law of Kepler is that planets move in elliptical orbits, with the sun at one focus of the ellipse. The second law says that in this elliptical orbit, planets sweep out equal areas of the ellipse in equal time increments, and the third law says that there is a constant,

, where T is the period it takes to complete one orbit and R is the major axis of the ellipse, that is the same for all planets in the solar system.

Some claim that G can only be measured experimentally, and such experiments usually rely on sophisticated set-ups and devices. Strangely, though, there seems to be a more direct route to measure G through Kepler’s 3rd Law, which then brings up deeper questions about what G actually means.

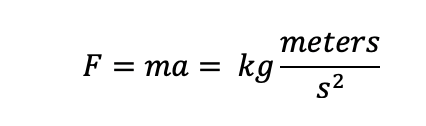

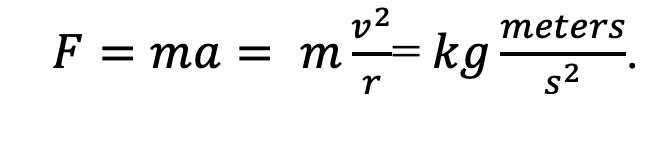

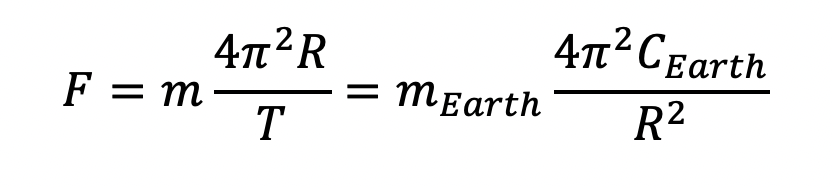

Let us start with one of Newton’s most basic laws and equate it to the units it uses:

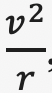

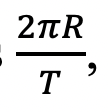

Now, given that Earth’s orbit has a nearly circular orbit (the ellipse has a very low eccentricity, which approximates a circle), we can assume that the acceleration is equal to

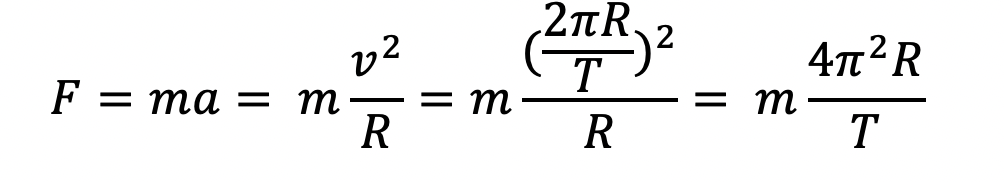

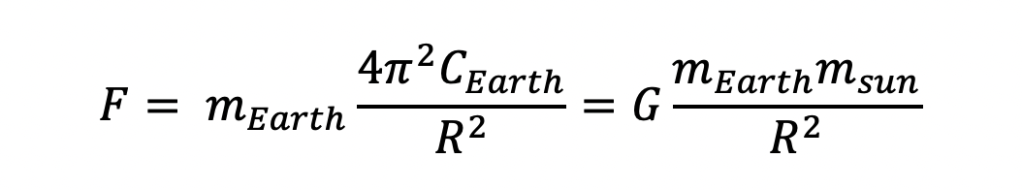

, which is the centripetal acceleration for a circle. So, plugging that in to the above formula we obtain:

So we still have the same units as the first equation, which checks out.

Now, we can assume that the velocity of a nearly circular orbit is

where R is the radius of the nearly circular orbit and T is the period of the orbit.

Then,

Utilizing Kepler’s 3rd Law, we assume

is a constant that we call CEarth, so inserting this constant as well as an additional R2 term in the denominator to compensate for the additional R2 term we insert in the numerator, we now obtain:

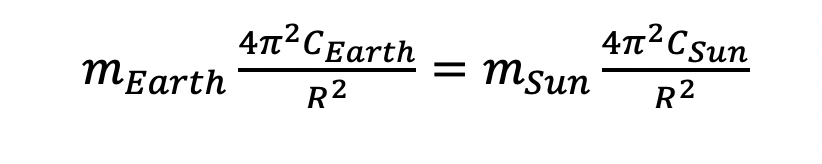

Isaac Newton established that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction, so the force that the Earth experiences from the sun must be equivalent to the force that the sun experiences from the Earth.

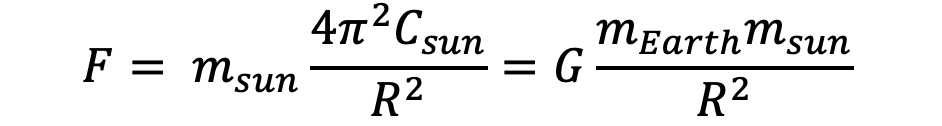

Csun is not an observable quantity like Cearth, since the sun does not orbit around the Earth.

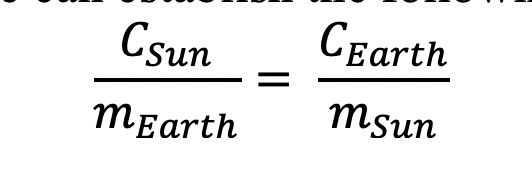

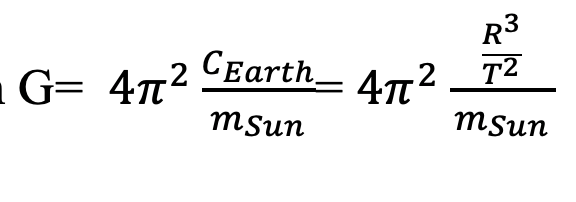

Through algebraic manipulation, we can establish the following:

Now let’s multiply the above by

and set equal to a new constant, G:

Let’s substitute G into our original equation that describes the gravitational force of the sun on the Earth, where Msun has been inserted in the numerator to compensate for the Msun inserted in the denominator contained in the term G:

For the sun, we can use the same substitution to get, where Mearth has been inserted in the numerator for a similar reason:

And thus, we get the same force experienced by the Earth and sun due to gravity, using the same terms.

The calculated value of G with sophisticated experiments and elaborate devices is the following:

6.674×10−11 m3⋅kg−1⋅s−1

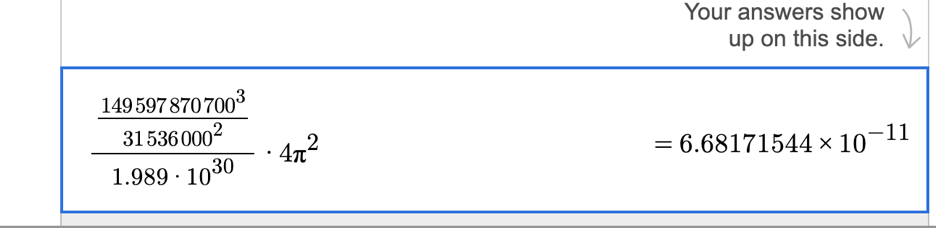

However, we can also get this value using the measurements in

Using some of the known values for the radius between the sun and Earth, period of orbit, and mass of the sun,we get a very close approximation to the value for G that is currently accepted.

But what about when one object does not revolve around another- why should the gravitational constant still hold, since it seems to be dictated by the

term which implies orbital motion?

It’s amazing to me that the gravitational constant holds no matter what the masses are and even if they are stationary to each other, since the above procedure shows how G is derived from the

term that implies orbital motion, a motion that is obviously absent between two stationary objects.

For 2 stationary bodies, the T squared term is meaningless, since there is no orbital motion and hence no period.

Perhaps the T squared term has a broader definition than just the period of an orbit. There is also a way to calculate G from quantum mechanics and the wave equation, which presumably does not depend on T squared and that leaves G dimensionless, though I would still like to understand how the T squared term relates to the quantum mechanical derivation, if at all. Furthermore, I have ignored the true meaning of gravity, which is only apparent in General Relativity as the curvature of space and time geodesics rather than as a Newtonian force. However, the same question still holds: how can the simple Newtonian derivation of G using orbital periods still be upheld and connected to quantum mechanics and general relativity ideas to explain the existence of gravity in 2 stationary objects?

If anyone can shed light on this serious mystery, a mystery with gravity, don’t hesitate to comment!